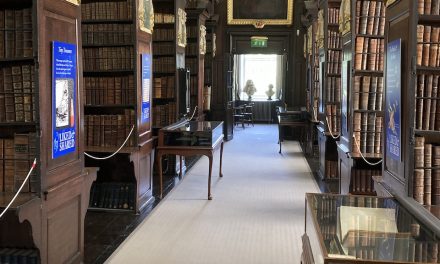

In this article, Jake Hearn and Fariha Sikondari explore the stories told in, and the process of curating, Middle Temple Library’s summer exhibition: Islam, Astronomy & Arabic Print.

The Library’s summer exhibition germinated from an idea to showcase some of Middle Temple Library’s lesser-known printed and manuscript collections that embody the presence of the Arabic and Islamic worlds across Europe between the 14th and 18th Centuries. It tells the story of the emergence of Arabic print culture that flourished in the printing houses of London and Oxford nearly a century after Johannes Gutenberg’s revolutionary press. It goes on to explore the interest in the Quran across major European cities during this epoch of wider fascination into Islamic scholarship. And ends by looking at the impact of Islamic astronomy on writers and thinking in England during a period of dramatic growth in scientific and religious understanding of the universe.

The story of Arabic printing begins in 1524. Robert Wakefield’s Oratio de laudibus & vtilitate trium linguarum, a Latin treatise on the merits of Arabic, Aramaic, and Hebrew, published by Wynkyn de Worde of Fleet Street, is considered the first work in England to contain the presence of Arabic type. Given the infancy of moveable type, revolutionised by Gutenberg’s press some 70 years prior, the few Arabic characters that are included in the book are misshapen and lack the necessary cursive nature of elegant, flowing Arabic script.

The intersection of Arabic printing in England and the Inns of Court existed through the early modern jurist and scholar of England’s ancient laws, John Selden (1584-1654), a member of the Inner Temple, Called in 1612. Selden’s 1614 Titles of Honor – a monumental work devoted to peerage law, heraldry, and genealogy – included several Turkish and Arabic words, which were indexed at the end of the book in a section titled ‘the more special vvords of the Eastern Tongues’.

Selden’s later titles, De successionibus in bona defuncti (1631); Mare Clausum (1635); De jure naturali(1640); and Eutychii Aegyptii (1642) included typeset Arabic characters that were somewhat disjointed and contained several large gaps where the printer had attempted to provide enough room to fit the Arabic script neatly alongside the Latin print. The substantiality of Arabic print in the latter title of 1642 was enough, among some scholarly circles, to render it the first Arabic book printed in England.

The boom in Arabic printing, after the hiatus of the English Civil War, brought with it a renewed interest in the Islamic world. Attention was focused on writers and thinkers in the scientific sphere such as the astronomer Abū al-ʿAbbās Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad ibn Kathīr al-Farghānī (800-870). One of his principal works – Jawāmi ‘ilm al-nujūm wa-usūl al-harakāt al-samāwiyya (Compendium of Astronomy and the Principles of Celestial Motions, written around 833 and 861) – had such an impact across Europe that it was published and translated no fewer than five times between 1137 and 1669.

Middle Temple Library owns a copy of Jacob Christmann’s 1590 translation, which he titled: Muhamedis Alfragani Arabis Chronologica et astronomica elementa. Christmann’s translation upheld the integrity of al-Farghānī’s writing and his intention of producing a short introduction course in astronomy based on Ptolemy’s Almagest. It described the main facets of astronomy: the heavens, the planets, the stars, the sun, the moon, and the earth, including their movements. He also provided a list of well-known lands and cities. His aim was to present his work in a simple style, without complicated mathematical calculations, which favoured simplicity of thought over scientific technicality.

Middle Temple Library’s copy of astronomica elementa contains marginalia in the form of manicules and bracket marks. William H Sherman posits that: ‘[Manicules derive] from the Latin manicula, simply meaning “little hand,” and that really captures what it is without getting into the messy business of what it does.’ With regards to the latter, two questions immediately arise: what function do they serve? And, who drew them in? Both questions are not easily answered.

The function of the manicule present in books across the early modern period was a varied one: from marking noteworthy sentences to highlighting problematic passages, it gives scholars today an insight into the minds, reading habits, and early modern readers’ interaction with books. In the example of astronomica elementa, the marginal annotations draw out the significances of this book as a vehicle of scientific change and the impact of Islamic science on wider Europe. As to who drew them in remains a mystery.

We decided to put some of the Qurans that Middle Temple has in its collection into the exhibition, as European scholars during the Middle Ages and Renaissance period took an interest in learning Arabic to translate the Quran. The exhibits include an Italian translation, a Latin translation and two English translations.

One of the main Quran exhibits is a version translated into English in 1734, by George Sale, who was a lawyer and member of Inner Temple. It was regarded as a fairly accurate version as Sale consulted authentic Islamic sources to write commentary of the verses. It was well received by both non-Muslims and Muslims

The other English translation is a contemporary version translated by Dr Musharraf Hussain. I thought this would make a valuable addition to the exhibition for those unfamiliar with Islam. It contains moral lessons from the Quran and explanation about the context of verses. This version is usually kept in the multi-faith room on the 3rd floor. It was also important to include the Qurans in the exhibition as the revelation of Quran birthed Islamic scholarship.

I tried to make the exhibition a bit different and incorporate a small sample of Quranic verses that relate to science and astronomy. There are audio links to the verses so people can listen to the recitation of Quran and links to further detailed explanation of verses. The idea behind this was to enable the audience to engage in the exhibition and to contemplate the same verses that the early Islamic scholars and astronomers would have contemplated. These exhibits are also an opportunity to really learn and understand more about Islam, as I have found that some contemporary Islamic exhibitions tend to lack this. I tried to focus the exhibition on Islam, rather than the culture and traditions of Muslim territories.

In Islam, there is a link between understanding the universe around us and understanding God and therefore Islamic scholars endeavoured to investigate the design of the universe to deepen their connection with God. It is interesting to note that later European scientists, Newton, Kepler and Galileo, also believed that the perfection of the design of the universe was a result of one perfect being, a Creator. Newton wrote extensively about religion and commented that, the creation of eyesight requires the knowledge of optics, and the creation of hearing requires the knowledge of sounds, which he concluded pointed to man being created by an intelligent being.

A great scientist from the 10th Century, Ibn al-Haytham, known as the ‘father of optics’ pioneered the use of scientific methods in observing the universe. He was a rational thinker, who was clearly influenced by the Quran, as the Quran encourages the use of logic, reason and intellect to seek the truth of the Creator. His works and scientific approach had a huge influence on renaissance scholars and has been cited in the later works of the European scientists, mentioned above.

When researching this exhibition, so many interesting areas relating to Islamic heritage came up. For example, it is not well known that Timbuktu was a major centre of learning in the Islamic world between the 13th and 16th Centuries. However, it was closed off to Europeans until the 19th Century and generally inaccessible to travel to and so it became a mythical place for Europeans.

It was also interesting to see the significant role that women played during the Islamic Golden Age in the advancement of science and mathematics. Mariam al-Astrulabi refined the astrolabe, which was used to accurately measure the movements of celestial bodies. Many women managed madrasas and centres of learning. In the 9th Century, Fatima al-Fihri founded the world’s oldest university in Fez, Morocco. European philosophers and Orientalists travelled to the University of al-Qarawiyyin to seek access to precious Arabic manuscripts. These remarkable women, among many others, left a lasting legacy which still benefits the world today. The Quran places an emphasis on seeking knowledge and this no doubt had an impact on the lives of these inspiring pioneers of the Islamic Golden Age.

As you can see, it was a fascinating exhibition to work on. There are so many aspects to it, ranging from history, religion, philosophy, linguistics, to maths and science; we hope people will find it interesting and thought-provoking. The exhibition delves into Islamic heritage and Oriental scholarship and shines a light on the great scientific minds and scholars of the time.

The exhibition runs from May – September 2023. An online version of the exhibition can be found on the library’s webpage, which includes our promotional video about the Quran: www.middletemple.org.uk/library/library-exhibitions

Jake joined Middle Temple in August 2021 as Assistant Librarian. In his role, he curates the library’s specialist United States research collection; teaches classes on finding and navigating legal information; and contributes to the library’s enquiry service. Outside his role at Middle Temple, he serves on the editorial board of Legal Information Management journal (Cambridge University Press) as Vice Chair and has published and lectured widely on the intersection of the legal information profession and Artificial Intelligence.

Fariha Sikondari works at Middle Temple Library, where she manages the Ecclesiastical Law Collection and creates the annual bound index for the Consistory Court Reports. Prior to working at Middle Temple, she worked at several law firms