Seán Enright and Master Michael Ashe

In the Michaelmas Term of 1871, two young men went up to Trinity College Dublin. One was an outstanding scholar, the other graduated with a bare pass and entered the King’s Inns, Dublin, to read for the Bar. The barrister was Edward Carson, the scholar was Oscar Wilde.

Carson made his reputation in Ireland and later in England. The fall of Wilde’s prosecution of the Marquess of Queensbury for criminal libel owed everything to Carson’s advocacy. An extract from that cross-examination gives the flavour of the men.

Carson: Do you know Walter Grainger?

Wilde: Yes.

Carson How old is he?

Wilde: He was about sixteen when I knew him.

Carson: Did you ever kiss him?

Wilde: Oh, dear no. He was a peculiarly plain boy. He was unfortunately extremely ugly. I pitied him for it.

Carson: Was that the reason why you did not kiss him?

Wilde: Oh Mr Carson, you are pertinently insolent.

After that, it was all downhill for Wilde, and his case collapsed. Later that day, Wilde was arrested and prosecuted for indecency and went to prison, where he wrote The Ballad of Reading Gaol. Carson scaled the heights of law and government.

One of Carson’s other cases deserves mention. Archer Shee, the naval cadet, was wrongly accused of stealing a five-shilling postal order. The case was later dramatised for the theatre (The Winslow Boy), a movie and several books. None does justice to Carson’s skill and determination. In its final stages, all hinged on Carson’s short and brilliant cross-examination of the sub-postmistress. Unlike some modern advocates, Carson did not claim to be great. Still, his reputation as the outstanding advocate of the age was promoted by those whose opinions mattered: FE Smith, Marshall Hall, and Lord Atkin.

The Home Rule Crisis

In the years leading up to the Great War, the Irish Home Rule Bill was progressing through Parliament with every prospect of becoming law. Carson was then the leader of the Unionist party, and resistance in Ulster coalesced around Carson, who appeared at a series of vast public meetings in Ulster and England. The fears of the northern loyalists related to religious and political liberty, which, given Ireland’s history, was a legitimate concern. The second issue was even more fundamental: loss of citizenship. Carson was first to sign the Ulster Covenant, which resolved to use all means as may be found necessary to prevent home rule in Ulster. The Covenant was signed by nearly every adult loyalist in the north. This was rebellion, in all but name, and in Northern Ireland, an army of 100,000 strong formed to fight for Home Rule. Carson, though desperate to avoid civil war, sanctioned an arms landing of 30,000 rifles and six million rounds of ammunition.

While the arms ship was still at sea, the news hit the tabloids, and some of the conspirators got cold feet, and the arms ship was briefly diverted. Carson was consulted and gave the go-ahead. The arms landing took place under the cover of darkness, and the guns were distributed to every part of Ulster. Carson’s army now had the means to resist home rule in the North. Every part of this enterprise was unlawful: raising an army, drilling troops and importing arms. In London, arrest warrants were drawn up, and the names of Carson, FE Smith and many Tory MPs were in the frame. In what can only be described as a failure of nerve by the government, those warrants were never signed and issued.

In southern Ireland, the Irish Volunteers emerged to fight for the establishment of home rule. Between these two armies stood the British Army. Another wrinkle the government had failed to foresee was that within the British officer corps, there was a deep-seated reluctance to move against the northern loyalists. The Curragh mutiny of 1914 was the moment when it became apparent that the army could not be relied upon.

With the Home Rule Bill awaiting royal assent and the country on the brink of civil war, the Archduke Ferdinand and his wife were assassinated, and the Great War began. Carson and the Home Rule leaders called upon their supporters to defer Home Rule and join the British Army to fight in Europe, and that is what happened.

First Lord of the Admiralty

Carson served as First Lord of the Admiralty in 1917, during the submarine crisis, which almost brought Britain to the point of defeat. It was during this time that the Admiralty developed the convoy system, which would prove decisive. Although Carson’s management style was hands-off, and he rightly did not claim credit for this innovation, which owed most to an analysis by a junior naval officer. Although years later, Lloyd George would claim that it was he, Lloyd George, who solved the problem in a single morning. ‘The biggest lie’, wrote Carson, in his usual forthright style.

After the Great War

Ireland and the maintenance of the Union were Carson’s great preoccupations, and his disappointment would be great. The south of Ireland would gain independence, while the north would remain part of the United Kingdom. A split along ethnic and religious lines foreshadowed other breakups in the empire.

Carson was the only politician with the clout at Westminster and the credibility in Northern Ireland to be the premier of the new state. Still, he made it clear he would not stand and went to the Lords before the partition of Ireland became a reality. It is fair to the memory of Carson that he reminded the loyalist leaders that they had a Catholic minority and should show them they had nothing to fear. In this, he would be disappointed.

The Lords

Carson was the last member of the King’s Inns, Dublin, to become a Law Lord as the Irish Free State came into being and ceased to be part of the United Kingdom. In his maiden speech, he attacked the Government over the Treaty creating the Irish Free State, which he regarded as a betrayal, pointing the finger at Birkenhead, the Lord Chancellor. Lord Birkenhead took offence and used the moment to develop a rule that the Law Lords should not take part in public affairs outside their judicial office. Carson’s career as a Law Lord was otherwise undistinguished, and it was poor health that led to his premature retirement.

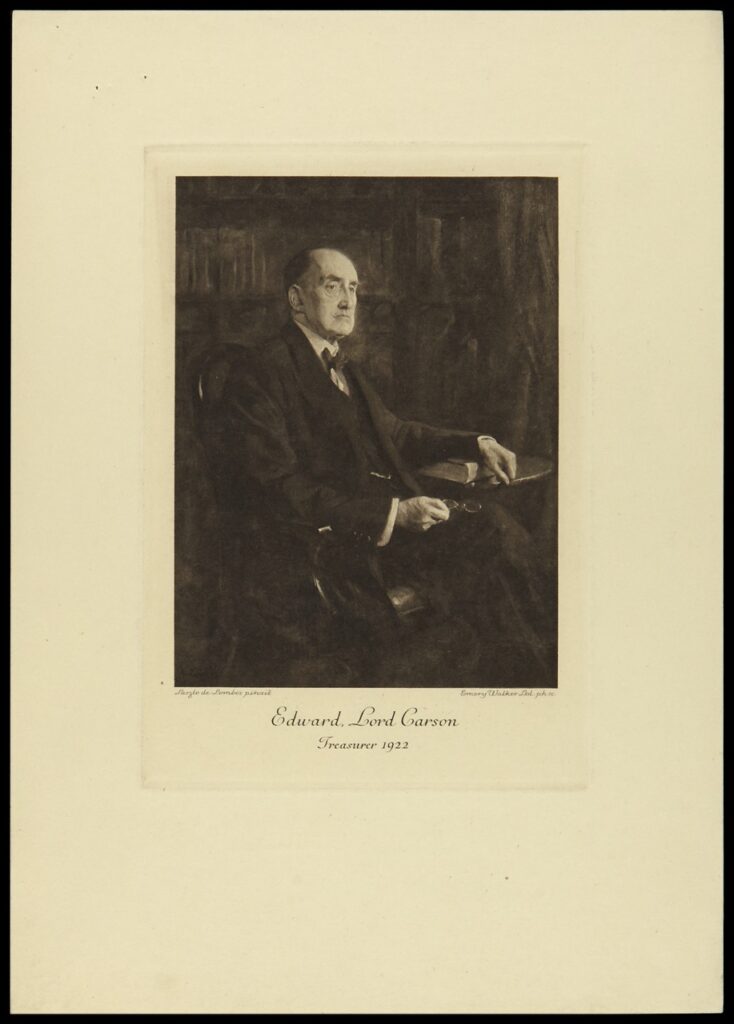

Treasurer

In his year as Treasurer of Middle Temple, the minutes of the Inn do not record any significant matters. The records of the Inn give the flavour of the times: Masters of the Bench would not be charged for cigarettes or cigars at dinner, and a lady barrister member could bring a guest on Guest Night for dinner, as long as they were not a male.

Lord Carson died in 1935 and was given a state funeral. Carson’s achievement in Ireland was to preserve the citizenship and cultural identity of the northern loyalists, but at a cost to the Catholic minority. The backlash came in 1968 with the civil rights movement, which quickly turned into an ugly sectarian conflict. This was part of his legacy in Ireland, but hardly his responsibility.

Carson’s reputation as an advocate can be distilled down to the Wilde case and the defence of Archer Shee. His crisp, structured style of cross-examination marked him out as a forerunner of modern advocacy.

As a parliamentarian, he was scrupulously straightforward but more effective in opposition than as a minister. The motto on his arms was in keeping with his character: Dum spiro spero – while I breathe, I hope.

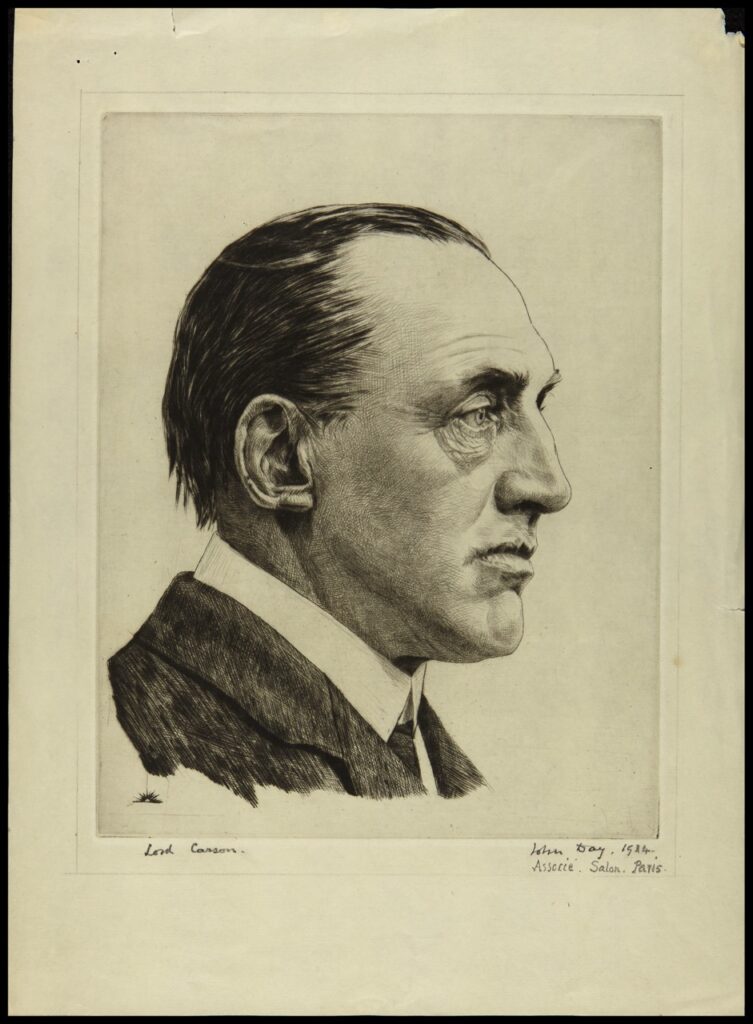

His portrait hangs in the Parliament Chamber.

His Honour Judge Seán Enright is a Circuit Judge sitting in Crime at Peterborough. He is the author of several books, including those in the field of Irish history.

Master Michael Ashe practices at the Bar of England and Wales and the Bar of Ireland.