‘Does classical music have to be entirely serious?’ was the title of a lecture that Alfred Brendel gave at Darwin College, Cambridge, in 1984. It was a startling choice of subject for a man who was widely considered to be the most serious pianist of modern times, yet it served to illuminate the many layers and great depth of a musician who received little formal training but delivered remarkable insights through his performances.

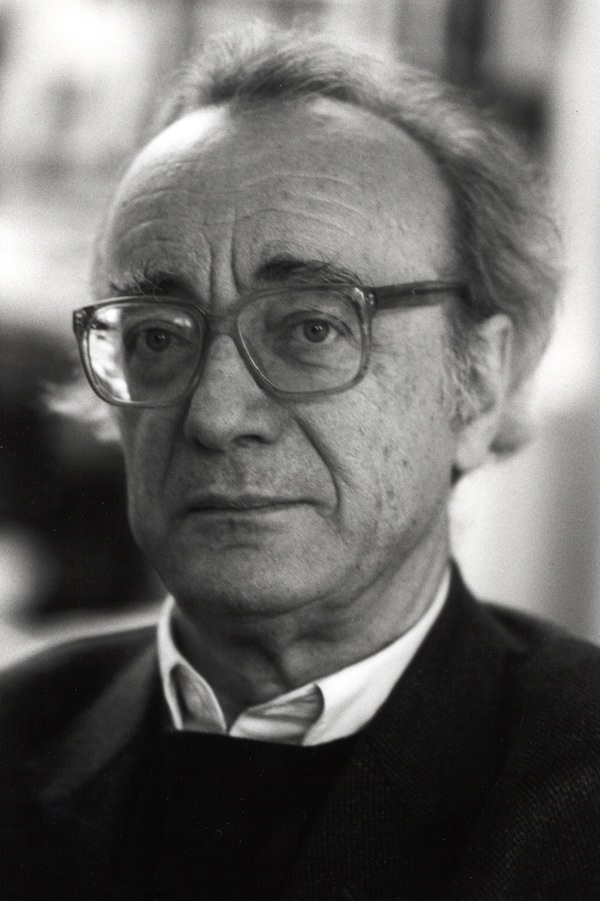

While he looked like a highbrow professor, spoke with a thick Austrian accent and performed concerts that could on paper appear devoid of any light relief, Brendel was a man with a quirky personality who loved life in all its seriousness and absurdity, wrote nonsense poetry, was inspired by the Dada art movement and collected kitsch at his home in Hampstead, north London.

Brendel could have excelled as a poet, painter or author; indeed, he achieved success in — and drew inspiration from — all these fields. Instead, he became a colossus of the piano, striding across the concert platforms of the world with a determined sense of purpose. He had come to prominence slowly, almost as if by stealth. He had no burning ambition to be famous, but in his mid-twenties decided that he wanted to be a pianist of stature by the time he was 50, and thought that he probably had the potential to achieve that aim.

Even with such far-sighted vision, he seemed to progress only gradually at the start of his career, leaving him wondering if something was wrong with him or with almost everybody else in the profession. There was no list of regular famous chamber music partners from his early days, and, astonishingly, there were two years in his early twenties when he did not even own a piano, and played only occasionally when visiting friends. Yet where a pianist such as Vladimir Horowitz had two topics of conversation, the piano and himself, Brendel had his vast hinterland — coupled with his anarchic spirit — to fall back on during difficult times.

Brendel was unusually tall for a pianist, to the point of having a gangly deportment, and often suffered from back problems. He had an individual sense of style and was never seen without his trademark heavy spectacles, while his high forehead was accentuated by a central raft of wayward hair. His facial grimaces in performance were legendary, although they would break out in a toothy smile as he acknowledged the audience’s applause. His frequently bandaged fingers paid tribute to the dedication of his practice.

He was largely self-taught, listening to tapes and recordings of his own playing and that of musicians he respected. This appreciation of others was a continuum throughout his life, and his writings constantly acknowledged the influence on his own interpretations of conductors such as Bruno Walter, Wilhelm Furtwängler and Otto Klemperer, and the baritone Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau (with whom Brendel made three recordings). They showed him that playing the piano was a matter of turning the piano into an orchestra or a singer and only rarely letting the instrument speak for itself.

He grew up in an age in which an artist would choose between the classical tradition of Haydn, Beethoven and Schubert, or the more pyrotechnical world of Chopin. He made one recording of the latter and thereafter stuck resolutely to the former, although Liszt’s highly excitable music continued to feature — to the extent that as recently as October 2016 he was demonstrating passages from the composer’s great Sonata in B minor during a lecture at Kings Place in London. He loved playing Bach, but regretted never learning the Goldberg Variations. He also had a passionate interest in Busoni, whose music (notably the opera Doktor Faust) he championed, and Schoenberg, whose piano concerto was the only 20th Century work that he regularly performed, recording it as early as 1957.

Brendel came to attention through his early recordings in the 1950s, notably Prokofiev’s Fifth Piano Concerto, and by 1959, he had embarked on the first recording by any pianist of Beethoven’s complete piano works for Vox-Turnabout. Curiously, his work on the 32 sonatas was concluded on his 32nd birthday in 1963 — he recalled that it was a cold winter morning in a dilapidated Viennese mansion, with the logs in the fireplace crackling so loudly that they had to throw them out of the window into the snow before the recording could proceed. By the 1990s, when Brendel recorded the Beethoven sonatas for a third time, recording facilities had improved somewhat.

Despite his success on disc, for many years, his relationship with concert audiences was strained and characterised by a mutual wariness. In part, he made little effort to endear himself to them, but they also took a long time to identify with the depth of his intellect. One American critic wrote of coming away from a Brendel performance ‘greatly enlightened as to the music’s sinews, but unwarmed by its flesh’. His technique was meticulous, bending the final joint of his finger as it touched the key to achieve the perfect pianissimo. Yet some of his fellow pianists questioned his respect for the instrument. Daniel Barenboim once told Alan Rusbridger, who at the time was the editor of The Guardian: ‘He’s a great, great pianist, a towering intellect and a wonderful humanist — but he f***s up pianos.’

Brendel was regularly seen in the audience of London’s concert halls, as well as its theatres and opera houses. He took a keen interest in new music and would encourage young players to look at, for example, the études by Ligeti. He also admired Harrison Birtwistle and Gyorgy Kurtag, although he never contemplated learning any of their music.

Unlike many performers, Brendel did not continue until he dropped dead, nor did his career fizzle out as the deprivations of old age took their toll. Instead, he stopped giving concerts at a time and place of his own choosing — the Musikverein in Vienna in December 2008. It was preceded by a final concert in London with the Philharmonic and Charles Mackerras in October that year. Characteristically, he avoided a flamboyant farewell, performing one of Mozart’s deepest and most mysterious early piano concertos: No 9 in E flat (K271). ‘It was utterly unshowy yet mesmerisingly elegant and nimble; devoid of affectation yet packed with nuances that suggested a teeming inner emotional world,’ wrote Richard Morrison in The Times, adding that the work’s Viennese minuet ‘was even more remarkably delivered: almost a recollection of how Brendel’s immense personal journey had begun’.

That journey had started in 1931 in Wiesenberg, northern Moravia (now part of the Czech Republic), where Alfred Brendel was born of Austrian, German, Italian and Czech descent. He was no prodigy. There was very little music in the house, and much of his peripatetic childhood was spent following his father, Albert, through various occupations — architectural engineer, businessman, resort manager — around Yugoslavia and Austria. As he would often say: ‘I was not a child prodigy or Eastern European or Jewish as far as I know. I’m not a good sight-reader, I don’t have a phenomenal memory, and I didn’t come from a musical family, an artistic family or an intellectual family. I had loving parents, but I had to find things out for myself.’

On Krk, an Adriatic island, he encountered what he called more ‘elevated’ music. ‘I operated the record player, which I wound up and put on the records for the guests of the local hotel, which were operetta, and I sang along and found it to be rather easy.’ He was six when his father became director of a cinema in Zagreb, where Alfred was enthralled by the movies of Charlie Chaplin, Harold Lloyd and Buster Keaton. Here he made his first stage appearance — as a sabre-rattling general, complete with fez, in a children’s play at Zagreb’s opera house. He also had his own phonograph and became interested in the new pop music coming out of Berlin. His normally serious-minded mother, Ida (née Wieltschnig), unwittingly inspired a lifetime of devotion to inspired nonsense, including the poetry of Lear and the art of Dada, when she read him the words of one of those pop songs: ‘I tear out one of my eyelashes, and I stab you, then I take a lipstick and paint you red.’

During the war one of his aunts was shot as a partisan and Alfred was sent to dig trenches. He suffered from frostbite and was taken to hospital, from where he was rescued by his mother. Later, he spoke of how fortunate he was never to have joined an army, his wartime experiences having left him a permanent sceptic. ‘The experience of war, bombs, people proud to be political ‘believers’, the preposterous voices of Hitler and Goebbels on the radio, the sight of Jews wearing yellow stars and the experience of a war closing in on where I stayed with my mother left a store of information in my memory, information that told me in hindsight what the world should avoid being.’

Afterwards the family settled near Graz, where his father, who entertained his children and later his grandchildren with conjuring tricks, now worked in a department store. Alfred entered the Graz Conservatory. By the age of 16 his formal training, bar attending a handful of masterclasses with Edwin Fischer and Eduard Steuermann, was over. Instead he recorded himself playing using a ReVox tape-recorder, listening to his performance and self-correcting. ‘I still think that for young people today this is a very good way to get on,’ he said in later life, ‘and it makes some of the functions of a teacher obsolete.’ However, he still thought that he would become a painter.

He gave his first public recital in Graz at the age of 17. It consisted of only piano works containing fugues, one of which he had written himself. A year or so later, his watercolours were exhibited in a one-man show in the city. When he went back to Graz in 1998 while making a television documentary, he was astonished to find that his paintings had not been destroyed. However, his career was probably determined when he entered the Busoni competition in Bolzano, Italy, in 1949. He placed only fourth, but his prospects were sufficiently encouraged that he decided to pursue the piano above all else. The next year, he moved to Vienna to escape his mother’s disappointment that he had not studied for a degree.

His first concert review in The Times came in 1958 for a concert in London at the Wigmore Hall, in which, as well as some Schoenberg and a group of pieces from Parthenia, he performed Liszt’s Sonata in B minor and Beethoven’s Hammerklavier Sonata. After pointing out some minor infelicitations, the anonymous critic concluded: ‘His performance was miles above the average account of [Liszt’s] elusive masterpiece; it was brilliant and heartfelt and rhetorically acute.’

In 1960, Brendel married Iris Heymann-Gonzala, an Argentinian who studied singing in Vienna and later became a potter. They had a daughter, Doris, who became the lead singer of the band the Violet Hour before developing a solo career. They divorced in 1971 and Iris died in 1977; according to Doris, she ‘never really recovered from my father divorcing her’. Brendel then made his home in London, where, in 1975, he married Irene Semler (known as Reni), a former model who worked for a German television company in Britain. He and Irene had three children: Katharina, a marketing manager; Sophie, who works at the V&A; and Adrian, who became a professional cellist, occasionally appearing with his father.

During the 1950s and 1960s Brendel’s career progressed slowly — often not helped by the highbrow nature of many of his programmes, including lengthy Beethoven cycles. ‘Looking back on it now,’ he said in 1969, ‘I feel that it may have been good for me that I got off to a slow start. It gave me more time to work on big repertory and to develop as a human being.’

By the end of the 1970s he was being increasingly recognised and appreciated beyond the piano cognoscenti. In 1983 The Times devoted an editorial to his Beethoven cycle in London, declaring: ‘It seems as if the intellectual musical life of the city has been concentrated for a brief span into this recreation of Beethoven’s exploration of the human condition.’ Thereafter, a Brendel concert was one of the hottest tickets in town.

Meanwhile, he became a familiar figure in the literary salons of London and would stride briskly across Hampstead Heath, carefully wrapped in a coat, woolly muffler, gloves and a beret in winter, like Beethoven on his regular afternoon walks in the Wienerwald. He also kept a countryside retreat in the depths of Hardy country in Dorset, where he would swim serenely in an indoor pool. He was never remotely complacent about his achievements, continuing to study and perform his beloved classics, forever believing in the possible development of his potential, musically and technically.

He refused to think of himself as a teacher, but worked with some of the most talented of the next and subsequent generation of pianists, including Imogen Cooper, Paul Lewis and Till Fellner, with Lewis describing their sessions as ‘more musical than specifically pianistic’. Cooper told how on one occasion ‘we spent a full 20 minutes working on a single chord in a late Schubert sonata, he with demonic intensity, I with a kind of rigid terror until I got it exactly right’.

Although Brendel well understood the difficulty of speaking and writing about music — explaining that the real message was in the performance — he published several perceptive books of essays on music, musicians and the peculiarities of the pianistic trade, and regularly contributed articles to periodicals such as The New York Review of Books. Poetry first came to him on a flight to Japan when a poem ‘emerged’ about a pianist growing an extra finger so that he could point at and ‘expose an obstinate cougher in the hall’ as well as ‘beckoning to the lady in the third row’.

He was awarded an honorary KBE in 1989, and in 2010 won Gramophone magazine’s lifetime achievement award. He was one of only a handful of pianists to be made an honorary member of the Vienna Philharmonic. After retiring from the concert platform, Brendel continued to be as busy as ever, particularly giving illustrated lectures. These could be very dry and required immense powers of concentration on the part of his audience, but rarely could he resist turning to the keyboard to illustrate a passage, giving younger audiences who perhaps had never heard him live the opportunity to savour a sample of an artist from an earlier generation. Retirement was not all plain sailing, however. ‘What I didn’t foresee were the physical annoyances of old age, of which the breakdown of my hearing was the most inconvenient,’ he wrote in January 2016.

Brendel was an artist with greater charm in private than in public, who seemed an unlikely superstar in an age that often favoured dazzle and bravura over gravitas and determination. He could be nervous, jittery even. Being neither a perfectionist nor a virtuoso, he had to fight for each piece. However, his strength came directly from that struggle. Nevertheless, in his continual search for musical truth, he never heard a performance that completely satisfied him, and never played one that completely satisfied him either. In keeping with his love of the absurd and, in a sense, answering his own question about whether or not classical music should be serious, he enjoyed pointing out that the word ‘listen’ is an anagram of ‘silent’.

This obituary has been reproduced with kind permission from The Times.