Earlier this year, the Honourable Society of the Middle Temple congratulated His Majesty King Charles III on the occasion of his Coronation. Since the Inn’s inception, 28 monarchs have been crowned, including the present King. We look back at how these occasions have impacted and been celebrated by the Inn, and how law and justice have been woven into the symbolism and ritual at the heart of the Coronation ceremony.

The fundamentals of the modern Coronation stretch back over 1,000 years to the Anglo-Saxon kings of England such as Aethelstan and Edgar, and the latter’s Coronation in 973 is the first of which we have a detailed account. The essential elements of that ceremony survive today: the king was bestowed with regalia (including a crown and sceptre), swore an oath to maintain peace, administer justice and exercise equity and mercy, and was anointed with holy oil. This final aspect of the ritual can be traced back to the Old Testament, when kings such as Solomon – depicted in one of the Inn’s best-known paintings – were anointed by priests and prophets.

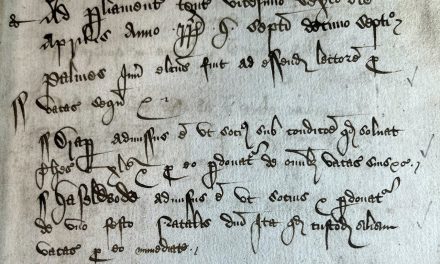

In the centuries which followed, the Coronation gradually increased in grandeur. The law took on an increasingly important role – the Coronation oath included commitments to uphold pre-existing laws (specifically those of Edward the Confessor), and from 1308 onwards the King was bound by his oath ‘to uphold the laws and rightful customs which the community of the realm shall have chosen’.

The Middle Temple came into being in the mid-14th Century, and the first Coronation to have taken place after this was that of King Richard II. This was notable for being the first to include a state entry into London on the eve of the Coronation – recognising the increased importance of the support of the City and its institutions. The King processed west from the Tower, and eventually along Fleet Street, passing the top of Middle Temple Lane. Music was performed along the route, and the conduits ran with wine – the new residents of the Temple would doubtless have been eager spectators and participants in this event.

These processions became a regular feature of Coronations for the next three centuries, rising to a height of pomp and pageantry under the Tudors. The Coronation of Henry VIII and Queen Catherine saw extravagant decoration along the processional route, and huge crowds turning out, no doubt including Middle Templars watching the King and Queen pass by the gatehouse. Decades later, the King was divorced and remarried to Anne Boleyn, who made her own Coronation procession through the City. In addition to the traditional music and fountains flowing with wine, elaborate structures were temporarily erected along the route, with classical and Biblical scenes recreated. On Fleet Street, the new Queen was greeted by a tower built atop the conduit, on the turrets of which stood the Virtues, promising not to abandon her, and at Temple Bar a choir sang.

Anne’s daughter, Queen Elizabeth I, is perhaps the monarch traditionally most closely associated with the Middle Temple, her reign coinciding with the zenith of the Inn’s flourishing and prestige, and her state entry was possibly the grandest in history. The Queen was carried on a litter decorated with cloth of gold, with Robert Dudley (whose armour is on display in the Prince’s Room) riding beside her. The Inn was well-represented in the procession, with Anthony Browne, Chief Justice of the Common Pleas, Richard Weston, the Solicitor General, and Sir Edmund Saunders, the Lord Chief Justice, all riding alongside many other judges and barristers. These three had all been appointed under Elizabeth’s sister Queen Mary I; within weeks all had been demoted by the new Queen.

The City had erected 11 triumphal arches along the route, with tableaux performed at each. The final such pageant was at Temple Bar, where, appropriately for the location, the Queen saw herself portrayed as the Biblical Judge Deborah. The urban elite lined the route to see their new Queen – no doubt many students, members and Benchers of the Inn were among them.

The tradition of the state entry and procession began to decline under Elizabeth’s successors. King James I and his son Charles saw their central relationship as monarch as one with God; their connection to their subjects was secondary, and such public appearances of correspondingly minimised importance. James’ reluctant procession was delayed by plague; Charles dispensed with the tradition entirely. This attitude would, ultimately, contribute to the Civil Wars which resulted in Charles’ toppling and execution, and the republican Commonwealth regime which followed.

The diarist and Middle Templar John Evelyn described the Restoration of King Charles II to the throne in 1660 as ‘an event cosmic in its magnitude’. The state entry to the City was revived for his Coronation in 1661, and many Middle Templars rode in the mile and a half long procession, including the Lord Chancellor, Edward Hyde, and the Attorney General, Sir Geoffrey Palmer. Four great triumphal arches were constructed along the route, including one representing the ‘Garden of Plenty’ on Fleet Street. The Inn erected a scaffold at the top of Middle Temple Lane for spectators, and bonfires were lit by the gatehouse.

However, the revival was short-lived, and the Inn would not see another such procession pass by for centuries. Perhaps fearing a negative reception from the populace, Charles’ Roman Catholic younger brother, King James II, did not make a state entry (a pity, as the Inn had just completed its new gatehouse) and nor did his successors, his daughter Mary II and her husband William III. Nonetheless, records indicate that the Inn had bonfires lit to mark both occasions, and some years into the reign of William & Mary a portrait of the new King in Coronation robes was commissioned.

William & Mary’s Coronation oath made important changes to the passages relating to the law – the ancient commitment to upholding the laws of Edward the Confessor was replaced by an undertaking to govern according to the statutes, laws and customs of Parliament, reflecting the constitutional changes which had taken place over the past decades, and which would set the framework for centuries to come.

For the two centuries which follow, the Inn’s records are largely silent on Coronations, although the accessions of Anne and George I were marked with new portraits of each monarch in Coronation robes, both of which hang today in Hall, and notable Middle Templars would have been involved in the Coronation ceremonies of the Hanoverian monarchs. When Queen Victoria was crowned in 1838, the Inn’s lack of engagement with the occasion raised eyebrows – a couple of years later, one Bencher expressed his concern that the Inn would mark the Queen’s upcoming wedding to Prince Albert ‘in a manner which might mitigate its discredit following the Coronation of 1838’.

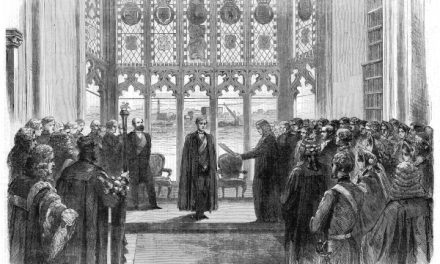

By the time Victoria’s son came to the throne as King Edward VII in 1901, things had changed. The new King had been a Royal Bencher since 1861 and served as Treasurer in 1887. The Inn threw itself into plans for the Coronation, which eventually took place in August 1902, illuminating the garden and giving a dinner for overseas lawyers in London for the occasion. A Royal Procession to the City followed in October, and a stand was erected in the gatehouse, with tickets issued to Benchers by ballot and a luncheon provided in the Parliament Chamber. As a lasting monument, the Inn also commissioned a large silver-gilt cup, of Elizabethan design, showing the profile of the King and scenes from his Coronation, as well as a set of silver-gilt standing salts.

This set the tone for subsequent Coronations – when Edward’s son George V was crowned, the Inn held a garden party and once again provided seating for Benchers in the gatehouse to watch the procession. George’s son, a Royal Bencher like his grandfather, succeeded his father to the throne in 1936 as Edward VIII, and the Inn was keen to mark it. He was invited in November of that year to attend a dinner or the garden party in the upcoming Coronation year, but this would not come to pass – he abdicated the throne just a fortnight later. The Inn immediately started planning for the Coronation of his younger brother, who ascended the throne as King George VI, once again arranging dinners and receptions for overseas delegates. The Temple Church choir attended the Coronation itself, and street decorations adorned buildings from Temple Bar to St Paul’s, with banners and garlands hung across the street, all to a design by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott.

70 years ago this year, Her Late Majesty Queen Elizabeth II was crowned. A Loyal Address from the Inn was composed and delivered to the Queen, and a Coronation Grand Day took place, attended by the Queen Mother (since 1944 our Royal Bencher), the Prime Ministers of Australia, New Zealand, Pakistan, South Africa, and Malta, as well as other notable guests such as Clement Attlee and Lord Rothermere. For the Coronation itself, Fleet Street was richly decorated once again, this time being ‘predominantly white with subsidiary colours of red and blue’. This was the first Coronation to be televised, and for the first time Middle Templars across the world could watch from their homes; no doubt many in London also flocked to the streets to watch the processions, as their predecessors had done for nearly six centuries.

This year, we saw the 28th Coronation of a monarch to take place since the inception of the Middle Temple. Over the centuries, the Inn has changed and evolved with the times, just as the Coronation ceremony, and the pomp and pageantry which surround it, have developed to reflect the prevailing historical winds. Despite this, at the heart of the ritual remain the central elements whose origins can be traced back more than a millennium, and the Inn reflected upon this rich history as we celebrated the Coronation of King Charles III on Saturday 6 May 2023.

Barnaby Bryan studied Philosophy at King’s College, Cambridge, and later qualified as an Archivist at University College London. He has undertaken archival work at various institutions, including Unilever’s corporate archive in Port Sunlight. He joined the Middle Temple as a Project Archivist in 2015, progressing to Assistant Archivist in 2016 before being appointed as the Inn’s Archivist in 2019.