“Fair winds and following seas”

A luminous presence has departed our lives.

This is a dreaded day, when I must encapsulate a vast presence in a few words. Reducing it to its core, Tim’s life was characterised by four things. Each is of equal importance.

First and foremost, there was his Pursuit of Excellence.

This pursuit began at the age of five for Tim, when he became a chorister at Durham Cathedral. The choirmaster would rouse the boys each day at 17:00 for rehearsal. Rehearsals were an arduous exercise. Each boy would have to produce the perfect performance. Any flaw in the voice would result in the student being held back and made to rehearse until faultless. A perfect performance required the seamless blend of timbre, articulation, dynamics, and pitch. The Perfect Note. This was the lesson Tim carried with him for the rest of his life.

Whatever case he fought, whatever position he held, the choirmaster’s voice would ring in his head, and he would find the Perfect Note.

As Leader of the Circuit, he would visit every corner of its reach. He would discover that many talented barristers could not take Silk because their work was confined to tribunals. References from tribunals were not given weight by the Silk’s panel. Tim’s efforts would change that.

As Chairman of the Bar, he would fight for better fees for those doing legal aid work. Tim championed the cause of the publicly funded Bar. He believed that those at the coalface of the Law mattered as much as those in private practice. As a result of those strenuous efforts, a government minister (who shall remain nameless) threatened him with Competition Law and bankruptcy proceedings. It did not stop Tim from achieving better fees for legal aid practitioners. Albeit that agreement was later dishonoured by the government.

As Head of Chambers, he led by example. There were occasions when serving the profession became as important as getting accolades for oneself. He found kindred spirits in Fountain Court. He was extremely happy there.

The second aspect to Tim’s life, was his Sense of Fun.

Tim had been diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes at just 17 years old. Believing always that he would die young, he led his life at breakneck speed. But it was not enough to confine himself to all things serious. He was full of fun, and a silly sense of humour always glistened beneath the surface.

One day, in 2008, whilst he was the Chairman of the Bar, he went to see a performance of Swan Lake. Inspired by what he had just seen on stage, he emerged onto Prince Albert Road, and as the people around him watched in astonishment, he performed his own pas de deux. He contorted an entire 6-foot-4-inch frame into little balletic bounces. Fortunately, not many members of the Bar witnessed his performance.

As a father, he was radiant. He would read me stories where he became the characters. He decided, one evening, to play Peter Pan. I told him he had to think happy thoughts to fly. He duly thought of yachts and flipped his body in flight. In the process, he dislocated his shoulder and went to court the following day with a so-called ‘tennis injury’.

Setting up the Bar Choral Society was in part a reflection of his fun-loving side. But also, he believed that excellence and discipline in one area of life would inspire creativity in other areas. He believed that if lawyers could thrive in their enjoyment of music, that would embolden their contribution to their profession more widely.

This takes me to the third aspect: his Sense of Duty.

So often, one sees success measured by the question ‘what do I have?’ Tim measured success by the question ‘what have I given?’ This commitment to service is what set him apart.

It underscored his philosophy in setting up the Keble Advocacy course. By instilling confidence and a sense of belonging to those at their most vulnerable stage, Tim believed he was firming up the foundation of the profession itself.

Tim never needed to advance through position. He had a thundering practice. In fact, by taking on successive years of leadership roles, he had to make time for his work through sleepless nights.

There were cold-towel days and nights when Tim would wrap it around his head to do justice to his client’s case. Never satisfied with rote recitation, he always challenged the jurisprudential basis for any so-called seminal rule. Stare decisis would fly out of the window as the best answer was sought. A strict return to first principles and a Dworkinian quest for the right answer is what made Tim a truly Herculean lawyer.

Beyond this, though, he was a master tactician. Hannibal’s defeat through sound strategy was understood. For this reason, his nickname at home was Fabius Maximus.

His sense of duty informed broader compassion. He would listen with keen ears and kind eyes to all manner of grief. He would respond with considered advice but also inject infectious humour, which made the problem seem all the smaller.

His sense of duty, though, could lead him awry. In 2010, he was flying home from teaching advocacy in Pakistan. At Islamabad Airport, he thought he saw Osama Bin Laden. Yes, in the Business Class Lounge, eating a tuna sandwich. Fuelled by duty to his fellow passengers, he informed the authorities and triggered a national security event. The airport was shut down, planes grounded, and the individual arrested. Half-eaten tuna sandwich strewn on the ground. Of course, this man turned out to be an English businessman, on his way home to his family for Christmas. But it took courage for Tim to make his report.

Which takes us to the final aspect of Tim’s life.

Well, it is completely obvious what Tim’s greatest act of courage was. The proverbial elephant in the room. The clearest act of real bravery: he married Sappho.

I will come back to my mother in a moment. But first, his abilities as a sailor.

Some might say, sailing itself: navigating unpredictable tides and fishing lanes is demonstration enough of courage. But, again, it was really sailing with Sappho, which required mettle. One summer, we ran headlong into a storm in the middle of the Channel. The sail snapped from the mast, the GPS and steering failed, and Tim was navigating by pure dead reckoning. Sappho had been suffering from sea sickness for about eight hours. Soaked to the skin, she asked, ‘Timmy! How much longer of this?!’ To which the misguidedly honest answer came: ‘Um. About ten hours’. Sappho then disappeared into the cabin, I thought perhaps to draft the divorce petition, but actually she emerged with a very large…hammer. Fearing for Tim’s life, I asked, ‘What are you doing with that?!’ She answered, ‘I am going to put a hole in this bloody boat!’ To which Tim’s ever-rational response was, ‘Well, I’m not quite sure what you’ll achieve by doing that.’

Luckily, we made it to France and Tim spent the rest of the holiday, paying penance, in Chanel.

Those who truly know my mother know her as a brute force of intellect. She forces you to face intellectual and emotional truths, whether you’re ready for them or not. As a slightly repressed public-school boy from North Yorkshire, I suggest it did require some courage for Tim to marry the intellectual and emotional bazooka that can be Sappho.

But Tim saw the ineffable sparkle, mischievous humour and deep well of wisdom which make up Sappho’s true nature. And he fought hard to make sure such qualities remained by his side forever.

As their witness to their 38-year marriage, I can testify it was a life full of adventure, laughter and intellectual dynamism. There was simply no such thing as being bored when in the company of Tim and Sappho.

Through his illness, Sappho carried Tim: physically, professionally and emotionally.

Perhaps it’s no surprise that as he lay dying in her arms, Tim’s very last words were to say to her: ‘Thank You.’

Motor Neurone Disease.

It eats away at the body bit by bit. First, his legs felt weak. He used a stick. Then a wheelchair. He fought his last case in court with a broken foot and broken rib because his legs had given out the night before. He told no one until the case was over.

Then the lungs. Normal breathing was impaired. At first, there was the rattle of the nighttime ventilator, but it would relentlessly progress. Night sounds would bleed into daytime struggle. He did not complain.

After that, it was his hands. They depleted the bone, which could hold nothing. He carried on working.

The body descended into complete paralysis. Muscle by muscle. Limb by limb. So it went. And so it went. He carried on. He dictated his book, chatted to friends and family and listened to opera.

When someone dies from a long illness, it is common to say: We will not remember them as they were when they were ill. That is not true for me. Of course, we remember Tim in his prime, but it was in the extremes of suffering that he taught the true meaning of courage. Not to remember this would be a disservice to his memory.

When invested with his CBE, Tim was required to choose a motto. He chose in virtute sumus, meaning ‘we go in bravery’. I cannot think of a better description for how Tim approached his last days, and to cite the Bard: ‘Nothing became him in his life like the leaving of it’.

And so, we come to the Supremum Vale. The final goodbye to this wonderful man. How best to say the valediction to a man who faced all adversity with so much hope and courage? Perhaps he said it for himself when he was given his lifetime achievement award: he ended his speech of thanks with a piece of music, whose words, when translated from Latin, were ‘I am looking forward to the life to come’.

So now, Tim is crossing the bar. He is setting sail on the high seas, standing tall at the helm, lungs full of sea air, face basked in the glow of an eternal sunset and an angelic tune on the wind. He is safe in the knowledge that he is deeply loved that he gave more of himself to life than one would have thought possible, and that he leaves behind lasting legacies on land. He is no longer in any pain and strong in his faith that what waits on the horizon is everlasting peace.

Fair winds and following seas, Papa. Godspeed.

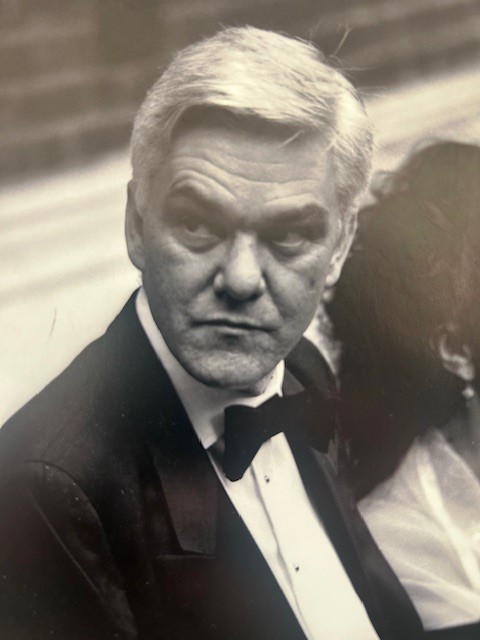

Tribute shared with kind permission from Master Timothy Dutton’s daughter, Pia Dutton