George Treby’s notebooks in the Middle Temple Library, Cases in the King’s Bench, 1678-1672, are a treasure trove for legal scholars and historians. The two manuscript volumes of proceedings in the King’s Bench (including some cases from the courts of Common Pleas, Chancery, the Old Bailey and Exchequer) run to almost eight hundred pages and provide more detail than contemporary printed reports such as those of Joseph Keble. They also contain numerous previously undeciphered insertions and marginal notes in a shorthand the young law student and fledgling barrister Treby clearly intended to be illegible to anyone but himself. Many of these consist of lawyerly – and largely pedestrian – queries, summaries, cross-references and updates (the latter revealing that Treby continued to consult these notebooks well into the 1690s). However, as I have discussed in a recent blog post, other shorthand interventions reveal sensitive, even scandalous, inside information about various cases and courtroom actors, including occasional references to shady and corrupt practices and gossipy and irreverent asides about some of the luminaries of the Restoration bench. This shorthand opens a window into the private thoughts of a precocious legal talent who would go on to become Recorder of London, Solicitor General, Attorney General and, finally, Chief Justice of the Common Pleas. Not least, as the two examples examined below illustrate, these carefully coded notations also shed new light on the political education of a man who would become one of Charles II’s staunchest opponents in the House of Commons.

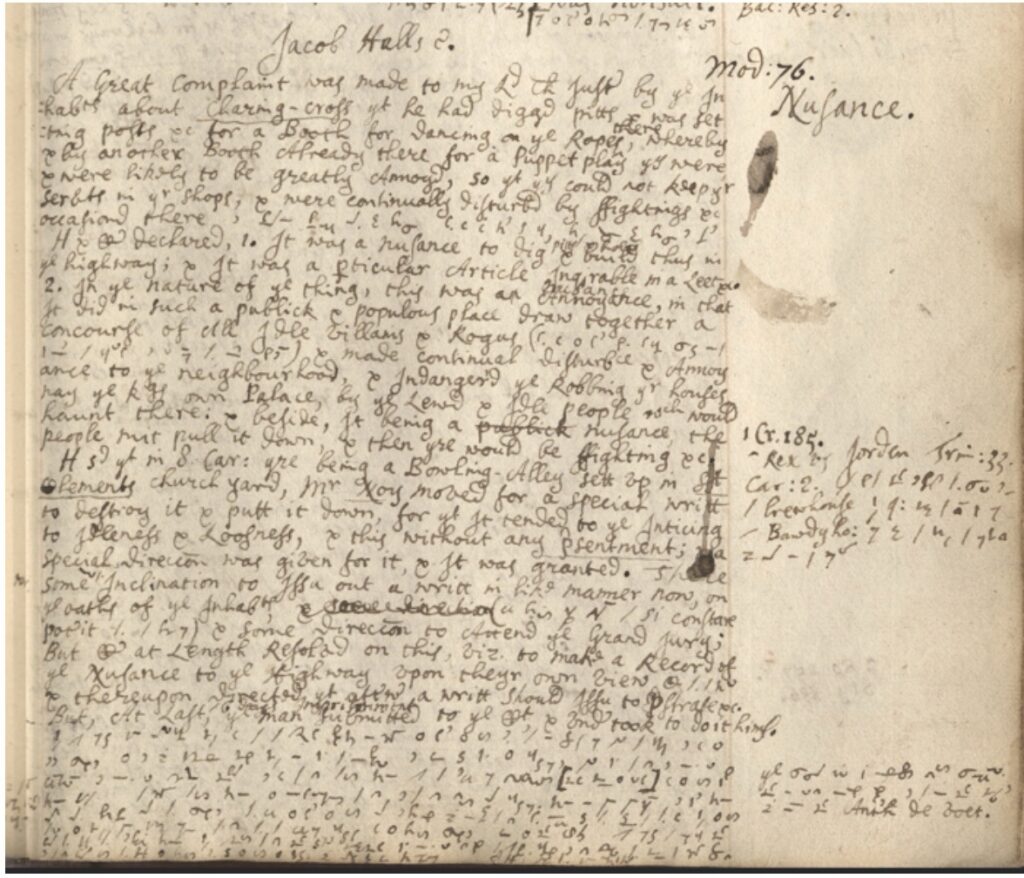

In October 1671, just after Treby had been Called to the Bar, he recorded the public nuisance case against the rope dancer Jacob Hall, a handsome and athletic performer whose underdressed displays of agility had made him a Restoration celebrity. Treby’s shorthand recounted how disgruntled Charing Cross neighbours had lodged complaints against Hall, who had been building booths, pits and posts for puppet shows and acrobatic displays, attracting ‘a concourse of idle villains and rogues’ and other ‘lewd’ people who disrupted business, corrupted apprentices and caused noise and disturbances at all hours. After initially agreeing to pull down his structures, Hall then repeatedly ignored orders to stop building, defiantly telling the court that ‘he would do it [continue to build] despite all the judges and that he did proceed.’ Hall and ‘his workmen’ were duly ‘brought in by the marshal and then as before’ (although there is no previous hint of this) ‘justified all by the king and my lord chamberlain and my lord Craven’s warrant. ’Hall brought out the big guns, declaring ‘that the king told him at the Duchess of Cleveland’s (with whom he lies) that he would bear him out.’ In response to this extraordinary claim, the judges ‘told him he misinformed the king and the king could not justify him in an annoyance and bade him enter into recognisance not to proceed to which he [Hall] said he would not dishonour his master the king so much as to assent to that’, vowing ‘till he brought an order from the king to the Chief Justice that he should proceed.’ Hall was promptly committed to prison by order of the court, at which point a message came from the king to Lord Chief Justice Sir Matthew Hale ‘to discharge him, but afterwards the king was satisfied otherwise by my lord Keeper, the attorney general and king’s counsel, to whom the court spoke…’

But despite the king’s apparent capitulation, Jacob Hall seems to have in the end completed construction of his pleasure grounds in Charing Cross. Treby’s shorthand gloss (in the margin) tells us: ‘the truth is the court dares not offend or displease this good and great man. ’While presumably a reference to the king, the sarcastic tone does not preclude an ironic characterisation of the uppity circus performer himself. The identities of the other principals, their names and titles carefully spelled out in shorthand, are also significant: Barbara Castlemaine, Duchess of Cleveland, was not only Charles II’s favourite mistress but was also widely reputed to be the lover of both the rope-dancer Jacob Hall and of young Henry Jermyn, the nephew and heir of the earl of St Albans, the Lord Chamberlain cited above. This is thus a veritable riot of inappropriate behaviour and relationships: Charles II was not only an adulterer (as everyone knew), but a cuckold, several times over, who preferred, and promoted, the claims of his unfaithful mistress and her lovers over those of the respectable inhabitants of Charing Cross.

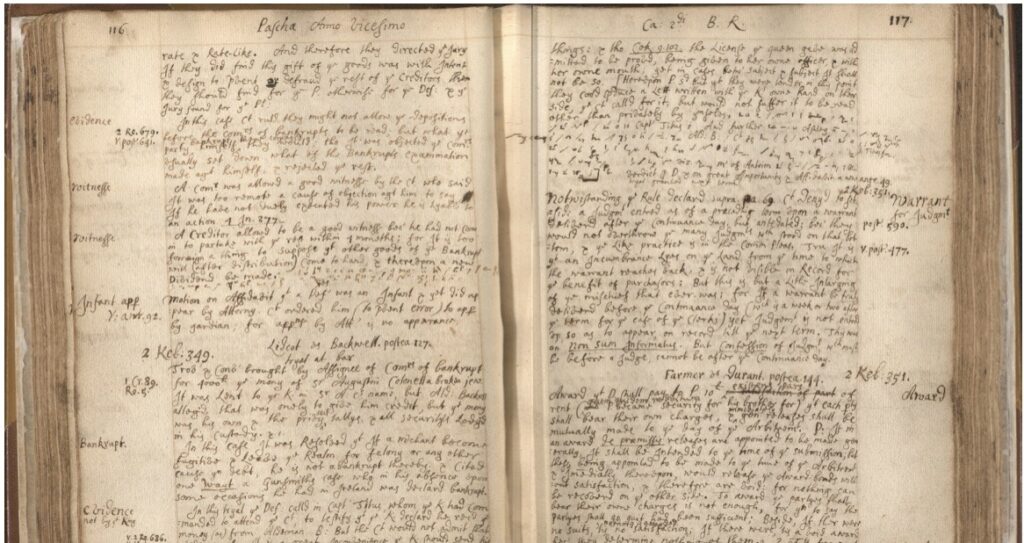

Perhaps even more shocking is the shorthand evidence of Lidcot vs Backwell, a bankruptcy case at the King’s Bench in October 1668 – a convoluted and obscure affair in which it seems that both parties were trying to recover loans that had been made to the king through proxies, but which had never been repaid. The defence called a witness, Captain Silius Titus, whom Charles II had sent to support the defendant’s claim that he had not received the money in question but paid it out to the king. The judges objected to admitting this evidence because the ‘authority’ of the monarch was ‘so awful as no Jury would go against it nor can It be expected he should keep in memory these minute things.’ At this point, the plaintiff chimed in, claiming that the king had provided him with evidence supporting his cause and ‘but that they were tender in this point they [the prosecution] could produce a Letter written with the King’s owne hand on their side.’ The ‘Court’ (i.e. the justices on the Bench) ‘called for’ this letter ‘but would not suffer it to be read other than privately by themselves.’ At this critical juncture, Treby takes up the narrative in shorthand (in bold):

‘Which done it appeared by their demeanour and concern that it was contrary to what he [the king] bid Capt Titus say And further when my lord Ashley came in and <amongst other things > said the king told him at first he had the money from Ald[erman Edward] B[ackwell] the court desired him to read the letter privately whereat he [Ashley] was a little surprised but said softly however this should not alter his testimony. The strong proof of that report that’

And here there is a blank space as though Treby were afraid to identify the king even in shorthand – ‘is given to lying notoriously’. To the right is this marginal gloss in shorthand, presumably intended as a summary or emphasis: ‘to understand from some that the letter was contradictory to Titus’s testimony.’ Treby also adds, explicitly linking the king’s personal failings to his political ones: ‘But a worse letter viz concerning [the] M[arquess] of Antrim was read in the afternoon in the House of Commons.’ This last is a reference to the controversial pardon and restoration of the estates of the Catholic nobleman Randall MacDonnell, 1st marquess of Antrim, widely suspected of being complicit in the 1641 Irish Rebellion. The other letter referred to presumably consisted of a royal promise, subsequently reneged upon, to grant Antrim’s lands to Protestant claimants.

Lord Ashley is better known by his later title, the Earl of Shaftesbury: a former minister of the king turned court opponent, widely viewed as the leader of the first modern political party (the Whigs). Silius Titus, a court supporter in the early days of the Restoration, would later go on to be one of Charles II’s fiercest detractors in Parliament. As for Treby (Sir George after 1681), he would become an MP in 1677, emerging as one of the leading members of the opposition to the crown in the House of Commons; in 1679 he was named Chairman of the Commons’ ‘Secret Committee’ investigating the Popish Plot and, by extension, Charles II’s government and entourage. In other words, opponents to the crown were not born but made, and not simply out of idealism or even opportunism and self-interest, but often as a result of what they had themselves seen and heard. In this case, the most formative first-hand experiences may have been regarding the so-called merry monarch – in Rochester’s famous verse, ‘a pretty witty king,/ Whose word no man relies on./ He never said a foolish thing/ Or ever did a wise one.’ Treby’s shorthand gives us a rare glimpse into how inside information – even gossip – that could not be recorded or openly expressed shaped the lives and careers of lawyers in both the law courts of Westminster and Parliament.

Andrea McKenzie is Professor in the Department of History at the University of Victoria, Canada. She has published on early modern English legal, criminal and cultural history, including trial, execution, murder, 17th Century shorthand, fake news and conspiratorial politics. Her most recent monograph is Conspiracy Culture in Stuart England: the Mysterious Death of Sir Edmund Berry Godfrey (2022).