In 2001, Peter Lantos retired as Professor of Neuropathology at the Institute of Psychiatry at Maudsley Hospital, King’s College London. For his 22 years in that post, he was also the lead clinician for neuropathology services of the NHS. He has written over five hundred scientific articles and written and edited textbooks. Born and studying medicine in Hungary, in 1968, he received a Wellcome Research Fellowship for one year to study at the University of London. At the end of the year, he decided not to return to Hungary and for his ‘defection’ he was sentenced, in absentia, to 16 months in prison.

In the winter of 1944, at the age of five, he was deported with his parents to the concentration camp of Bergen-Belsen, where he became prisoner 8431. The extraordinary story of his survival, and what happened both before and after, was brilliantly described in his memoir Parallel Lines: a Journey from Childhood to Belsen, which was published in 2006. Until 1944, he lived with his parents and his beloved older brother. The family were bourgeois Jews with a timber business. There was a large extended family in the town. His favourite cousin Zsuzsi was his playmate. They coped with the antisemitic laws, which had got worse, and which disallowed his clever brother’s entry to university. Hungary was nominally independent but had joined the Axis and provided hundreds of thousands of Hungarian troops for the invasions of Yugoslavia and of the Soviet Union. When the Soviet forces pushed westward, Nazi troops occupied Hungary in March 1944. A priority for them was killing Hungarian Jews. In May 1944, despite the Soviet forces continuing westward, and with the active assistance of the local fascist Arrow Cross, the deportation of Hungarian Jews began.

In quick succession, Peter’s family was forced into a ghetto and then transported to a collection camp. Apart from what they could pack in a suitcase, everything they owned was taken from them. Zsuzsi and her mother were put on the first train. It arrived at Auschwitz. Peter and his parents were on a different train directed to Austria. Here, his parents worked as slave labourers repairing bombed roads. In December 1944, they were deported to Bergen-Belsen. Belsen was a holding camp, not an extermination camp, although some 50,000 died there from starvation or disease, including Peter’s father. In April 1945, shortly before British troops arrived, Peter and his mother were amongst those put on a train which, some days later, was liberated by American soldiers. Many years later, when researching his book, Peter tracked down the American tank commander who rescued them, and he visited him in California.

That outline of the story omits many details, and it is Peter’s success that he sets out the whole story in the only way it can be—sparingly and emotionally devastating. Like other survivors, he has spoken many times to schools and institutions. In 2023, Scholastic published The Boy Who Didn’t Want to Die; it is a story of love, hope and survival written for children. It was The Times Children’s Book of the Week, was shortlisted for the British Book Awards for Non-Fiction Book of the Year in the category of Children’s Books and won the United Kingdom Literary Association Awards in the Information Books category in 2024.

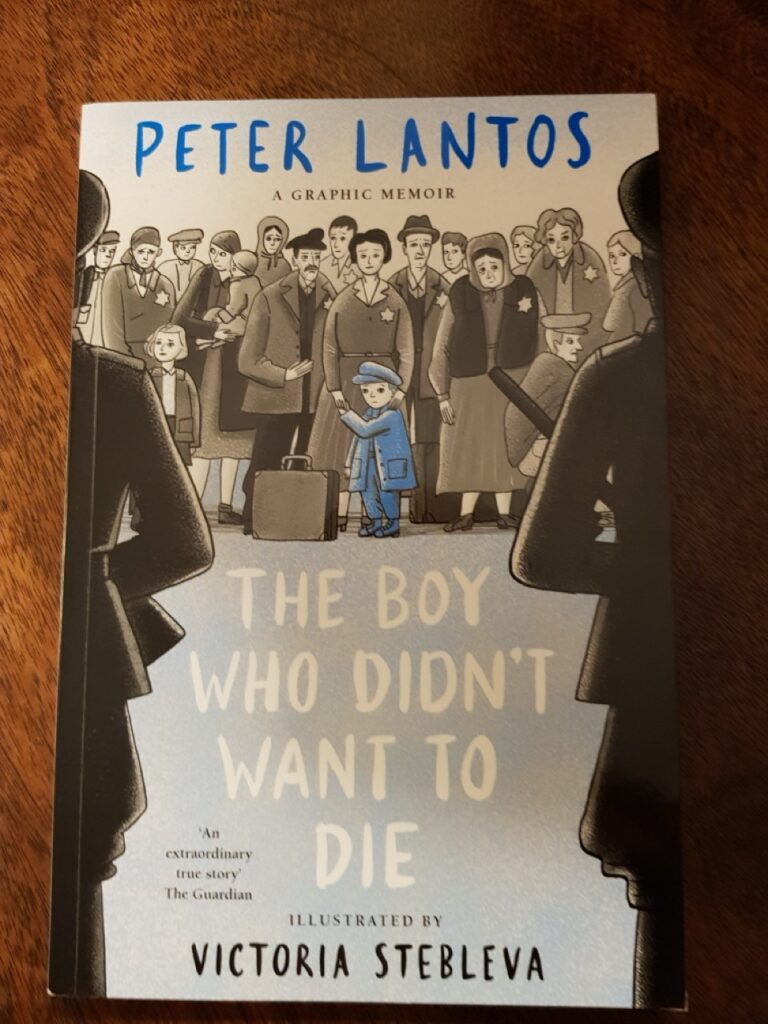

In January 2025, Scholastic published this illustrated version of The Boy Who Didn’t Want to Die. The original dialogue has been simplified but complemented with the artwork of Victoria Stebleva. The dialogue here is short and illustrative. It often relies on his mother or father trying to answer their bright young son’s constant questions. This brings out the inquiring mind of the future doctor and helps the reader along. Where were they, where were they being taken, and what was going to happen when they got there were the most difficult questions to answer. It is the sense of powerlessness which underlies everything, but the determination of the mother and son to live ultimately triumphs. The illustrations are excellent, conveying in the faces the fear, bafflement, tragedy and always the love between parent and child. The emotional impact for the reader is no less than when one reads the printed story.

One might ask: Why should I read another Holocaust story? There are two answers. The first is that there is not one story. There are infinite stories in the complex lives of the millions of victims. Peter’s is astonishing. Only a quarter of Hungarian Jews survived to resume their lives. In Peter’s case, he continued it without his father, brother and many family members, all of whom had died. The new life back in Hungary was not even as equal citizens since the new Communist state categorised the family as former capitalists. The second reason is to understand how it happened. Across Europe, it was local police who rounded up the Jews and handed them over, and local people who were getting on with their lives, which included participating in the transport and the maintenance of the camps. One must remember how easy it becomes to assist an evil at an arm’s length and to look the other way.

Master David Wurtzel has been a Bencher since 2001. He practised in chambers, primarily in crime, for 27 years. He has been particularly involved in the matter of vulnerable participants in the justice system. He contributes to Current Law Week, and is on the board of The Advocate’s Gateway.